Q&A with jonathan yeo and mette skougaard

Mette Skougaard is the director of the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle, Denmark. This interview took place in the months leading up to Jonathan's 2016 retrospective at Frederiksborg Castle, Jonathan Yeo Portraits.

The text is also included in the 2016 monograph In The Flesh, published by The Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle.

METTE SKOUGAARD: For many Danes it would be nice to have an explanation of who you are, why you decided to become an artist in the first place and why you have chosen portraiture as your field of art.

JONATHAN YEO: Well, the short answer would be that I wasn’t much good at anything else!

I went to a very academic school in London where I was generally at the bottom of every class except for literature and art. I loved drawing, and was regularly told off for doodling in my books when I should have been listening, but I actually found it easier to concentrate that way. In later life I was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, and if I was at school these days I might be treated with a little more patience. But strangely, being told to stop made me more stubbornly determined, as if drawing was my right and I wouldn’t let anyone take that away from me.

So I’d sketch my way through classes, and if I could get away with it, I’d draw caricatures of the teachers. It gave me a reason to look at them and appear to be listening, but also it would make my friends laugh, so it had several benefits. In retrospect it was probably the most useful thing I could have been doing, since really the one basic thing that you need as a portraitist is an instinct of how to draw and know where to subtly caricature faces.

When I left school at the end of the 1980s, there weren’t many options if you wanted to go and learn how to paint. At that time there was really only one art school in London teaching painting and pretty much everywhere it was seen as an old-fashioned genre and medium. So, I tried to make a living as a painter for a year and failed

miserably. It was a disaster. I didn’t know what I was doing and so was persuaded to study something rather than get a job. I did a film and English literature degree.

I wasn’t particularly engaged by the course but the workload was very light so it allowed me a huge amount of time for doing other things. I had access to a studio space owned by my grandmother and spent most of my spare time, weekends and holidays trying to paint. I also enrolled in some life classes. These were the closest

I got to learning anything formally.

While at university I got ill. I started showing symptoms of Hodgkin’s disease, which is a type of lymphoma, at the end of my second year of university. I was able to use painting as a way of taking my mind off the long illness; it became a therapeutic, almost meditative thing.

I was very lucky to be able to keep at it during a time when most people are forced to give up and get a proper job. Occasionally I’d do a good painting but not as often as I thought at the time. Most of them would look very basic now, because I really had no idea how to do it. Most of the people who offered advice, with my best interests at heart, would try to talk me out of it. In the middle of this difficult time I got an

interesting commission to paint Trevor Huddleston, who was a famous figure in the anti-Apartheid movement and a family friend. I slightly felt he’d suggested it out of sympathy but I didn’t want to waste the opportunity. The painting had an expressive, almost Cubist, style because I had just become interested in that period of Modernism. The result was amazing and surprised everyone, I think, including me.

MS: Looking at that painting, I seem to find a resemblance to some of the work by Lucian Freud. Is that right in your eyes?

JY: Well, that’s interesting because at that point I hadn’t really focused on Freud. I was aware of his work, which had been out of fashion and was really just beginning to be re-evaluated around that time. I wasn’t consciously attempting his style but it’s interesting in retrospect because clearly there were similarities there.

I did spend much of my time visiting galleries and looking at other artists’ work to try and see how they were doing it. I was visibly influenced by what I had access to, particularly paintings by David Bomberg, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and other twentieth-century artists at the Tate Gallery, which was the closest to where I lived at the time. My early style was therefore very much a fusion of the work I was seeing and it’s funny how, to me, those pictures I made seemed totally different from the work I produced later. It was only many years after that I started to notice the consistency.

Anyway the main upshot was that, because the Huddleston commission was widely seen, I secured a few more commissions. Not enough to make life easy but just enough to carry on the slow process of learning. In retrospect it was possibly the best thing that could have happened because doing portrait commissions was effectively the only way I could afford to keep painting.

MS: Did you develop your techniques while you were doing the commissions?

JY: Yes, that was exactly what happened. I learnt to warn my subjects that their painting might not resemble anything I’d done before and this gave me freedom to experiment. The portraits were a way of both honing my life painting technique and experimenting with different approaches. After about eight to ten years of working like that I started to explore working with photography too. Often successes happened by accident, so I got used to trying to make accidents happen. To this day one of the things that I love is to start a painting not with a white canvas but with a series of layers that evoke a certain aesthetic, colour scheme, energy, depth and atmosphere.

MS: The idea of giving the canvas a grounding was something that was first used by Renaissance artists. Do you see yourself inspired only by twentieth-century painters or do you also see a relation to the techniques and the ways in which artists worked in the Renaissance and Baroque periods?

JY: Actually I only found out later that that’s how they worked. I wasn’t studying those techniques, but I remember reading how some artists had a very bright red or sienna-coloured background, which would create a warmth in the painting, even if you covered all over it with many shades of grey. I’ve got many examples of paintings where that happened. What I did was to find my own way of solving problems that turned out to be very similar to how they’d done it in the past. Since I didn’t have any money if a painting went badly, I’d have to paint over it again to make use of the canvas. After a while I realised that, if you left a little bit of the underlayer showing somehow, it created an extra layer of mysterious depth.

At that stage if you ever did find a portrait or a figurative painting exhibition, it was very much dominated by artists doing photorealism without a concept behind it. Often they’d just be faithfully reproducing very weak photos. The painting was bad, not because of their lack of skill but because the photo they’d chosen was badly chosen, or wasn’t lit with any thought. These days I usually work from a combination of manipulated digital photos and direct observation but early on I concentrated on painting entirely from life. The advantage of that is it teaches your eye and brain how to take in information selectively and in total contrast to how a camera does, which is unavoidably democratic across its field of view. A mechanical device will pick up as much about the detail of the furniture or the floor as it will of a person’s face, whereas the way the human eye sees things is to react to someone’s appearance first and then to the less relevant things within our field of vision.

Whether you open your eyes, turn a corner, or even briefly glance at something, what you remember is not precisely every detail within your field of view, but the elements that matter to us most, and other human beings are the most important because they would usually give us the most immediate information. Our instincts would tell us instantly if someone we saw was a potential threat, a friendly stranger or someone you recognised. These are some of the primary considerations we instinctively check when we first observe any scene, and another face would be the initial source of this information. After that we’d take in other aspects – someone’s physical build is sometimes as relevant, sometimes not – and then certain other elements that your eyes take in are processed. It’s not conscious but we react, behave and even remember the scene afterwards accordingly.

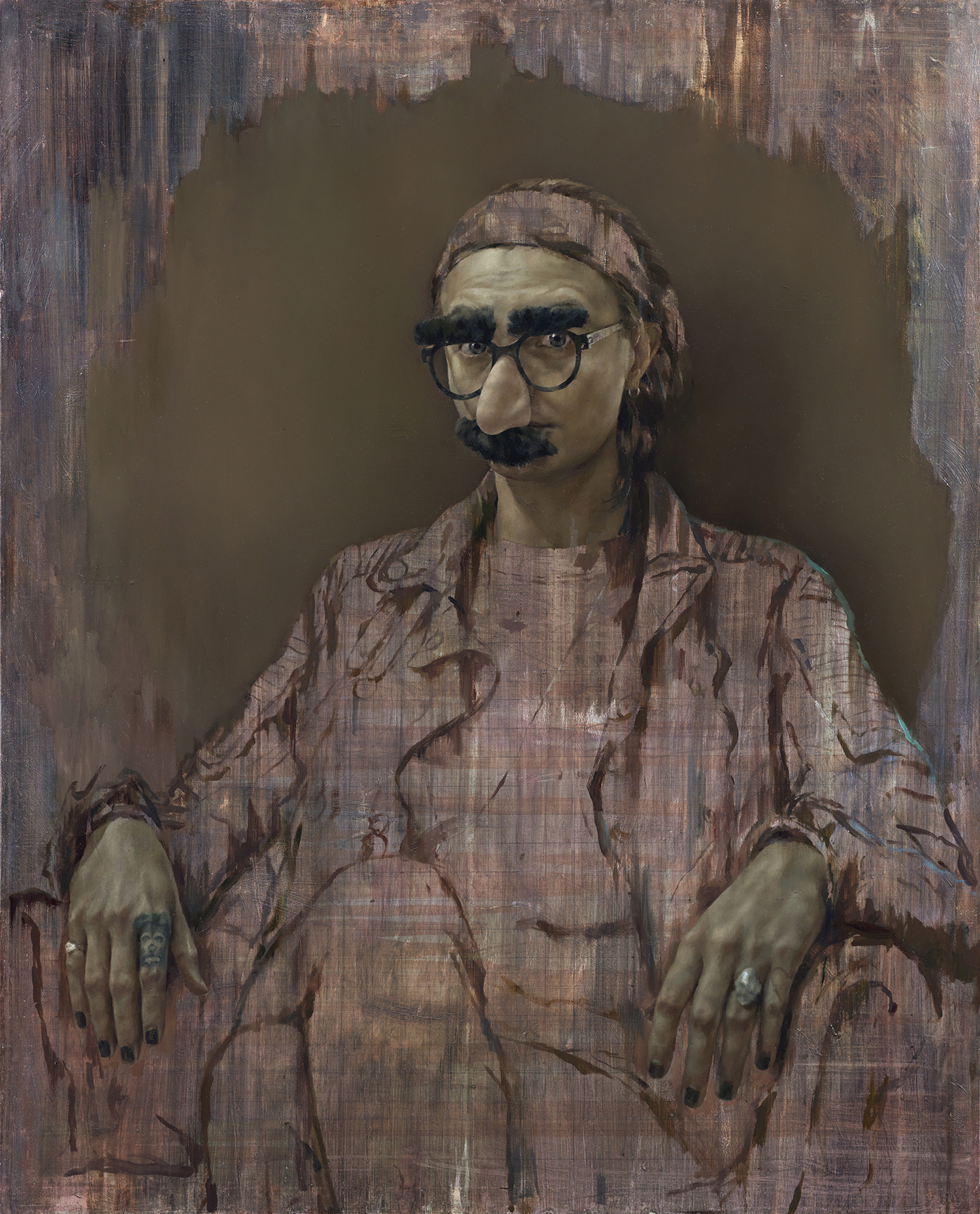

I’ve always believed that, for this reason, your mental picture of something is actually not at all like a photograph, but fragmented. Maybe mine is more so than most, but certain visual elements might be very precise while others very vague. We don’t need to see certain things in detail for our brains to accept that they are there. We assume architectural lines continue, or that patterns repeat without needing to check them all individually. I think all the way through my career this thing has been coming back, this idea that you don’t treat the whole picture evenly.

The more I understood how to look and paint, learning to manipulate the brush and media to reproduce what I saw in a deliberately painterly, slightly abstract or very realistic way, the more I became interested in conveying this idea. By experimenting with depicting different areas of a painting in contrasting ways, I found it to be not only a good method of demonstrating this idea, but also of emphasising certain key compositional elements and reducing the importance of others.

MS: It is interesting to see how your portraits show the process of creation. Is this intentional?

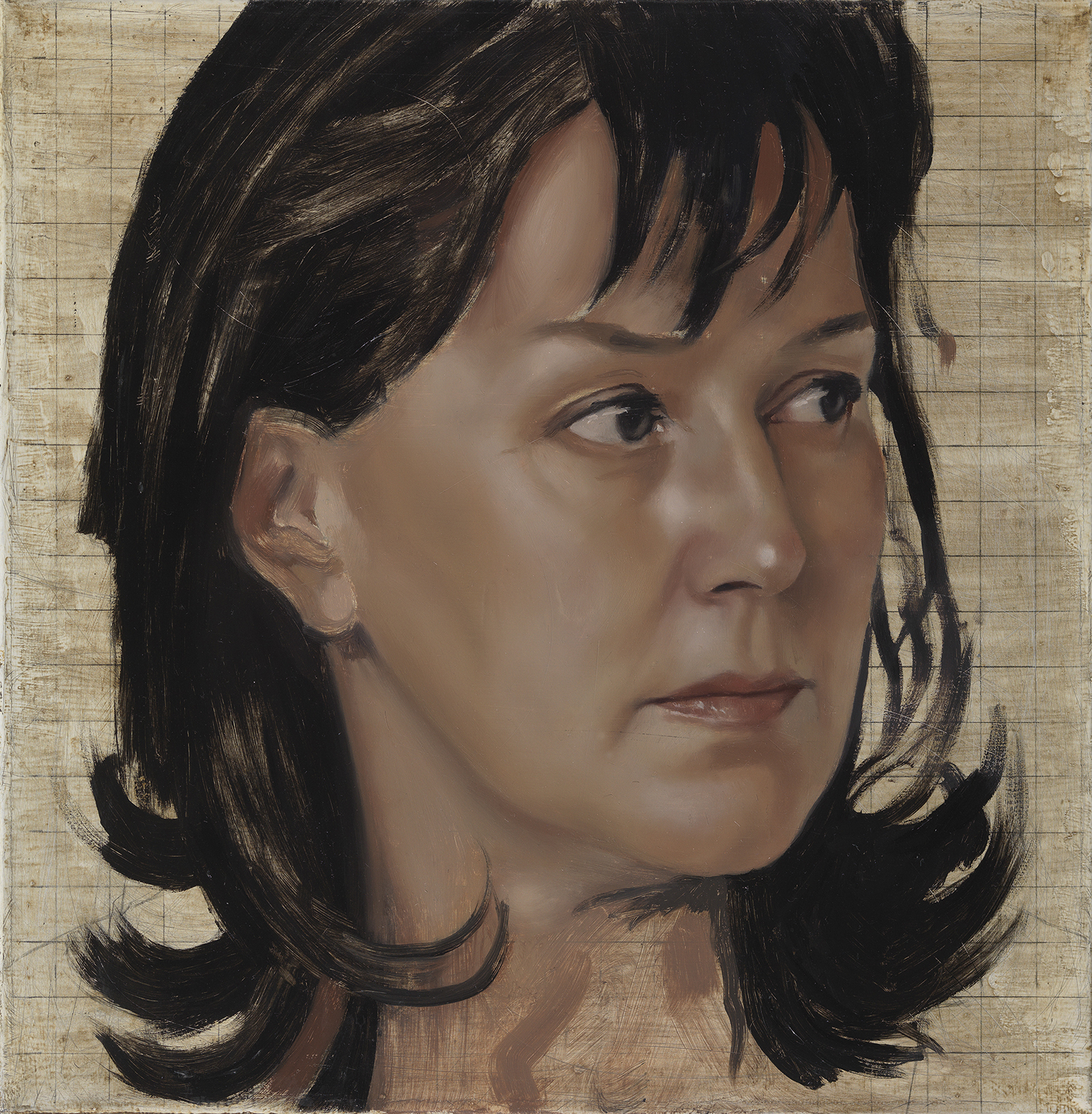

JY: Yes of course. By leaving some of the underlayers, backgrounds or even mistakes visible, I feel it aesthetically differentiates the work from both photography and stylised paintings of the past. I also like seeing a little of the working process and don’t mind others seeing it. I find the grid lines particularly pleasing. Many artists used squares or other measuring marks in the past to translate images from a drawing to a painting, and some still do, especially when working from photographs, but they’ll usually cover them up by erasing or painting over them. Maybe there’s a sense that they suggest too much reliance on mechanical methods or reduce the appearance of virtuosity. But it always seems a shame to me as it removes a potentially interesting compositional dimension.

I particularly like to use a grid when painting portraits as it adds an element of geometry to the surface. The very sharp lines juxtaposed with the skin tones somehow emphasise the different textures of someone’s face or body, especially when very smooth, and add a useful precision to parts of the painting. At the same time there’s variation so one painting will be different from another and I only started using this technique about ten years ago.

It’s become more logical to use photography in recent years because you can manipulate and distort photographic images digitally to create precise compositions before you start on a canvas. I was lucky in some ways that it wasn’t possible in the first decade that I was working because it meant I’d spent my early years painting from direct observation. I was aware that some artists were using mechanical aids back then but I never thought they worked properly. For me things like projectors merely exaggerate some of the deficiencies of the camera and distort things even more than the lens does already. My time spent drawing and painting from life meant I was more aware of the advantages but also limitations of photography when I did start using it.

It would be pointless to try and wind the clock back or attempt to dissuade young artists from making use of digital cameras but I do think it’s important that, if you’re going to use photography at all, you should really learn how it changes things and, above all, to work out what we see by actual observation.

MS: Do you regard it as a good thing that you haven’t been to art school, so that you have worked out your own methods?

JY: I did wonder that and early on I was convinced that it was a bad thing I hadn’t trained because I always felt that other people must have had a head start. In retrospect it may have been partly because I didn’t know how to do it that I therefore felt I had to work much harder than anyone else to develop my technique. Had I attended art school, I might have not concentrated and therefore learnt very much, might have got into complacent habits, and probably not ended up developing unusual solutions so, yeah…

MS: So, we’re talking about techniques in general. You’re saying you don’t have any fixed procedure, so the technique you use will depend on which person you are going to show to the world? Do you have a routine that you follow or are you influenced by the chemistry between you?

JY: A bit of both. There are some things that I’ll always do but other things that might change from one work to another. The style, colour schemes and extent to which I’ll complete a painting or leave areas abstract vary from one to another and I try not to plan these elements until I’m actually sitting in front of someone.

MS: What if the person says, I want you to show me in a certain way … how do you go about that?

JY: I think that happens much less than people expect because people do actually quite like the idea of opening themselves to someone else’s view. There are some people who are used to controlling their image and therefore it’s important to them and sometimes I’ll pay attention to their concerns but rarely very much. Occasionally you’ll get people making comments that are actually helpful and draw my attention to something I might have only noticed later or not at all. Either way it’s generally best to ignore suggestions and feedback, at least until I feel satisfied with a painting. I usually refrain from showing people the image until I’m happy with it and at the very least three-quarters finished.

MS: Have you ever experienced the model saying ‘I don’t look like that’?

JY: Early on it happened a few times but then I learnt that, firstly, you have to warn people it’s impossible to know how it’s going to turn out and, secondly, that they may not agree with it. I think over time you get used to and well-practised at working out who’s going to be difficult like that beforehand. If someone says something like ‘I put on a bit of weight recently but I’m going to lose it soon’ or ‘I don’t look my best at the moment’, then it’s much better to suggest they postpone the sittings until they’ve had a holiday or have been on a diet! The fact is these days a distorted portrait will be contradicted by photography. There’s no one that we paint who isn’t also the subject of at least a thousand photographs.

MS: So, what is it that a painted portrait can do that a photograph cannot do?

JY: Wow, that’s a big subject. They’re both brilliant in different ways. A photograph, at least until the recent awareness of Photoshop and digital manipulation, had a sense of authority, being a mechanical replica of an exact moment, even though it might only be depicting one exact aspect of someone’s personality. It’s also generally done in a single session, as photographers don’t tend to go back and photograph the same subject over and over, whereas with a painted portrait you have the opportunity to assimilate a whole series of impressions across a number of hours, days or even weeks. I feel it’s not restricted to the time when the subject is sitting in the chair, but the observation actually starts the moment I open the door to them or meet them elsewhere. You’re building a series of impressions, a sense of their physicality, their body language, their different moods and reactions and are filtering through everything every time you see them. A painting therefore has an inherent sense of time elapsing. It’s taking time to do the painting plus you’re noticing more things about them the more hours you spend in their company.

MS: But you developed on the theme of trying to combine many faces in one face?

JY: Yes. I’m not sure it’s quite right but I used to use the analogy of a photo being like an interview, a quick conversation, whereas the portrait is more like a biography: people’s faces, especially as they get older, betray far more about their whole life and their personality and what’s going on and you can’t help but form a whole series of impressions from the moment you meet them. They come into the studio and the way they react to things, that all feeds into the picture and, as you get to know them better, of course, over several sittings as well. Photographs are very unlikely to get the same subject coming back and back again, whereas a painted portrait pretty much demands it. Actually one of the problems I now expect is that the first day that someone comes to sit, even when they’re used to sitting for photographic portraits, they tend to be quite self-conscious, but I might only come to realise this when they’ve sat a few more times and relaxed into it.

One of the lovely things about doing portraits is you have people coming in maybe six, seven, eight times over a few weeks or even months and you therefore see them in a variety of moods. Everyone looks different on different days so you try to average it out or if there are several contrasting things that interest you, then try to show them all without making it look too convoluted. It works best when there’s a subtlety to it but I don’t always get it right. It’s very often only at the end of the project or later on you realise whether you were getting it right or not.

And the other nice bit, of course, is that the painting literally takes time to make. It’s not like a snapshot. So, you’ll be doing one side of the face and by the time you get down to doing the other side, it might be a few hours or even days later and things have changed. A painted portrait is also a record of time elapsing and that’s an important part of the definition.

MS: I think that’s a very important point for understanding your portraits and why they are so fascinating. What if you don’t like the person who’s sitting for you? Has that happened to you?

JY: It has happened. You might think the result is going to be a disaster but actually that’s rarely the case. On several occasions in the past I’ve been worried about portraying somebody as I see them for fear it’ll seem like I’m being negative or picking up on a characteristic most people wouldn’t like. Strangely, however, I have learnt it is always a mistake to change a painting because you think they’re going to see it in a certain way. Often the characteristics that some people might be embarrassed to show, perhaps they’re arrogant or overbearing or flashy for instance, are ones that the subject themselves are comfortable with. It’s always better not to try and second-guess their reactions and just channel whatever impressions you have into the work. If you do your best to be truthful it makes for a better portrait and usually the subject accepts that too.

In retrospect it’s often the ones I’ve been most worried about that have turned out to be the least problematic. You’d think that politicians and actors would be the vainest of all but, weirdly, they are often the easiest from this point of view because they are more used than most people to being shown in a negative light.

MS: So, what do you think defines a good portrait?

JY: I think a good portrait is a document of the relationship between the artist and the sitter and should shed light on both that couldn’t otherwise be fully captured by words or photography alone. The chemistry between artist and subject is key to the whole thing, partly because the work communicates a reassuring level of authenticity. It comes from real experience, one that’s filtered through the editorial process of the artist doing the recording. This is what’s especially relevant for a museum where there’s an historical angle.

MS: Lucian Freud said that resemblance is irrelevant in a portrait. Do you agree with that?

JY: I know what his point is, that it doesn’t have to be a photographic likeness to represent someone. I think that, like a lot of artists, Lucian’s brilliance was in turning his deficiencies, his lack of abilities, into a virtue. It’s sometimes visible, especially in his early work, that he wasn’t very good at drawing accurately. He therefore developed a method of taking very many days to make a painting – he made people sit 20, 30, 40 times – and eventually he would get it vaguely right. In the process he would often capture other more subtle elements that might have eluded an artist painting a portrait in just one or two sittings, so I think I know what he means. There’s often too much orthodoxy in portraiture and portrait artists have had a tendency to paint in an

unnecessarily traditional, straightforward, homogenised way. When the artist isn’t very good to start with it exposes this further. Maybe partly for these reasons the genre was widely seen as irrelevant in the latter half of the twentieth century and most contemporary artists wanting to make their mark tended to do other things.

It’s a funny thing to be working on something where you’re aware of both the pitfalls of trying to be too gimmicky or different for the sake of it, and of being too traditional and therefore irrelevant, but I try to navigate a course between the two. Portraits obviously need to resemble someone enough that there’s no doubt who the subject is, but they are best when representing more than just their surface appearance. They may also betray some of the artist’s personality too.

MS: What about the challenges of portraying a world-class actor or a public figure who knows so much about himself or herself and self-presentation? How do you find the essence of the person?

JY: That’s a very interesting question and one of the main areas I was keen to investigate in more depth here than in previous exhibitions.

Lucian Freud observed that ‘if you look different, I think you must be different, because what you look like is you, isn’t it?’, which is a nice summary of the portrait painter’s credo. For the portraitist, therefore, an actor presents a fundamental problem. The better they do their job, the harder it is for me to do mine.

Performers, actors and often politicians are in the business of deceiving us. They are trying to convince us that they are something they’re not, and their faces are a key part of this fraud. We expect them to be doing this and, in the case of actors at least, the better they pretend, the more we enjoy it. At the same time, in the back of our minds, we’re still conscious it’s a performance and we don’t necessarily mind if we’ve seen the same face playing other roles before. The portrait painter, however, needs to find a way of identifying the point at which the performance stops and the real personality of the performer reveals itself.

The portrait I recently made of Kevin Spacey as President Frank Underwood plays with this paradox. In the House of Cards show he’s depicting a fictional character, but one whose job we’re very much aware actually exists. We go along with the game because part of us wants to believe he really is the President, at least while watching the show. At the same time, you can’t help but acknowledge that it’s Kevin playing a part because, dazzling as the performance is, we recognise him from any number of entertaining deceptions in the past. Therefore, the portrait deals with deception as its subject, as the viewer again is left to figure out who is being represented: Kevin Spacey or Frank Underwood. Also, by unveiling the portrait at the Smithsonian

National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, where many of the national collection of real presidential portraits are housed, in the city where the ‘real’ politics goes on, I hoped to increase the confusion about what is real life and what is art. I wanted people to be aware of this paradox, which is at the heart of the challenge of taking someone from real life and making them into a work of art.

I think in recent years the awareness of truth and artifice in portraiture has become increasingly mainstream, even if it’s something most of us are not consciously aware of. On a weekly, if not daily, basis, we’re consuming, discussing and even making images and we’re also thinking about whether what’s being communicated is genuine. We use images of ourselves to project exaggerated versions of our lives, perhaps more

interesting, glamorous, clever, cool or talented than we actually are. We have become used to both wearing metaphorical masks and conveying enhanced versions of ourselves and we expect others to be doing likewise. At the same time, because everyone is becoming aware of an element of artifice, we may be deliberately or inadvertently revealing a little of the truth.

Obviously this has happened through the explosion of image-sharing via social media, and in the process the younger generations have become more adept at creating, reading, decoding and unravelling images of each other in a way that might previously only been considered in such depth by artists, photographers or art history students.

My series of paintings of Cara Delevingne were done very much in reaction to this realisation as it made sense for me to investigate this change in our visual culture (and mull over the possible future impact on painted portraits) by working with a subject who is synonymous with creating such images of herself and playfully sharing them with this increasingly sophisticated and knowing young audience.

Like Kevin, Cara is also a master of manipulation, having modelled and now gone into the world of acting. Her ability to transform made her a fascinating subject and perfect for a series of work, as opposed to a single image, in which I tried to capture her almost restless chameleon-like quality. Both these subjects, therefore, very much pose a challenge to me as a portrait artist in trying to capture their essences, but as a result I think I have produced some of my most interesting work, even though these portraits could perhaps be the most far off the people who they intend to capture due to the very nature of their subjects!

MS: Is there a secret behind the creation of a good portrait?

JY: If there is a secret – and this is a really annoying answer for the 20-year-old student – it’s basically that if you spend half your waking hours practising the same activity for 25 years, you’re going to get good at it eventually, whatever it is, and whether you’ve been taught it or not. People always say, when they hear you’re self-taught and didn’t go to art school, that they can’t believe it, as if it’s something that can be learnt only from established experts. Actually, what happened was that I wasn’t taught the rules so I never knew what I was supposed to do or, more importantly, not do. Some ‘rules’ I worked out for myself; many of them I might not have learnt much quicker if I had been in art school, but often I’ve had to improvise my own solutions.

So there are probably many parts of my technique that are not how you’re meant to work and this worried me for a long time. Gradually I realised that actually there must be certain aspects that are unique because no one else’s will have evolved in quite the same way.

MS: So what are your special techniques?

JY: For instance, the obvious one is the way the paint dries. In recent years painters have increasingly painted in multiple layers; they want materials that speed up the drying time and therefore demand painting media that dry as fast as possible. I realised early on that what I want to do, particularly with a portrait, is keep the paint as wet as possible because you want to work on a painting all day, and then come back the next morning and correct the mistakes and work a bit more. To model the skin tones in a smooth but complex way, I find it more helpful if you can work into wet paint for as long as possible rather than start another layer.

You have to go back a long way to find a generation of artists who were trying to achieve similar effects, several hundred years in fact, and the techniques are hardly used these days. A breakthrough came when I learned that, traditionally, Old Master painters added a tiny amount of clove oil to the linseed oil mixture. You have to be a little more careful with it but the advantage is it slows the drying time down from a day or two to a week or more. There are also ways of isolating the paint surface so the oil can’t evaporate but it gets quite complicated pretty quickly.

MS: Do you also have certain techniques concerning the use of colours?

JY: As I wasn’t taught what colours to use I’ve worked out a very simple palette that suits me and where I can quickly mix the colours I’m looking for without having to think about it. I mostly just use one yellow, one red and two blues. Rarely any other colours and never black. It may be why the colours are never quite lifelike in my paintings but I feel the colours always make some sense within the context of an individual work. I’m really always looking to find subtle ways of rendering skin tones lifelike while being a bit artificial too, if that makes sense. I love it when paintings seem somehow unnaturally real.

I sometimes reduce the colours so it’s almost black and white, but not quite. I still mix using the four colours I always use, and white, rather than black and white, so there is some variation but it’s very slight. When you do then introduce a tiny amount of colour, your eyes read it and take in some of the information about shape and form and reflection, which it would take from a colour image but your conscious brain is used to a simpler colour scale from photos, and therefore reads it as a black and white image. It therefore has the simplicity and aesthetic of a colourless photo, and we know it’s not pretending to be reality, but we are aware of it having much greater depth. When you get it right, it’s as if a black and white photo is suddenly coming to life. It also applies to the paintings where I skew the colours, making them almost entirely from yellow or green or pink shades. It allows you to accept it’s something from another reality but at the same time has an eerie quality as if it’s more real than something from the real world.

MS: When you imagine the visitors in Denmark coming to the gallery to look at your work what would you like their lasting impression to be? Which things would be most important for you?

JY: I think that portraiture is a genre that is very alive and is going to be increasingly relevant, at least over the next few decades, because we are now, certainly very recently, much more avid and daily consumers of portrait images, whether it’s in advertising or in magazines or on Instagram. We’re looking through and seeing portrait after portrait after portrait, and we’re often making judgements about people because of what they look like, not because of what they do or what they say.

By exhibiting these paintings, especially the recent Cara series, in these surroundings, in a museum dedicated to preserving and continuing the traditions of historically important portraiture, we’re inviting people to consider how relevant portraiture has suddenly become to many people’s lives. Hopefully they’ll see the connection

between how we are using this imagery in the digital era and the way in which artists were wrestling with similar ideas in the past. I’d love to think it will lead some viewers to speculate and investigate how it may change further from here.